DRONES AT SEA: MARITIME SECURITY THREATS TO GULF INFRASTRUCTURE

Nasser Saif Al Kuwari

The strategic landscape of the Gulf is increasingly shaped by the proliferation of maritime drones, which present a serious threat to critical infrastructure such as desalination plants, LNG terminals, ports, and submarine cables. These unmanned aerial, surface, and underwater platforms offer state and non-state actors an affordable, deniable, and asymmetric means of applying pressure and conducting hybrid warfare in maritime domains. Drawing on recent incidents in the Red Sea, Gulf of Oman, and along the coasts of the UAE, this policy brief analyzes the vulnerabilities in Gulf infrastructure and the evolution of proxy drone tactics. It proposes a triad of policy responses a GCC-wide alert-sharing network, investment in layered maritime defenses, and the institutionalization of joint regional drills. These measures aim to build strategic deterrence, reduce response time, and establish operational resilience against the growing threat of drone-enabled disruption in the Gulf’s maritime domain.

I. Introduction: A New Maritime Threat Frontier

The Arabian Gulf has been one of the most strategically vital maritime thoroughfares in the world for decades. In addition to being home to the world’s densest concentration of energy transfer terminals, it is also host to critical water desalination plants, international submarine cable networks, and the globally dominant supply of LNG energy. In fact, one-third of all oil by volume traded globally travels through the Gulf today. Gulf littoral states and the whole Gulf region are heavily reliant on these maritime infrastructures because they enable, directly and indirectly, the oil and gas sector, which underpins Gulf states’ economic lifelines. The high value of these maritime infrastructures, coupled with their concentration in many instances either on the coast or within striking range of some regional actors, has rendered the region more and more attractive for a new generation of asymmetric weapons platforms: drones.

This brief uses the term "maritime drones" to refer collectively to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned surface vessels (USVs), and autonomous underwater vehicles (UUVs), unless otherwise specified. These platforms vary in size, range, and payload capacity but share a common function: they allow state and non-state actors to project power in maritime spaces without risking direct confrontation or attribution. The threat of drones at sea is not new, but since 2019, these have expanded in frequency, technical complexity, and strategic impact. Today’s drones are not solely intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and monitoring vehicles but instead have increased precision, which enables them to cause material damage.

Drones can be used for precision kinetic strikes, interfering with logistics and operations, injecting malware into industrial control systems (ICSs), and ultimately becoming decoys in multi-platform attacks. Iran and its affiliated proxy groups have since 2019 used drones to target tankers, monitor Iranian and non-Iranian navies, and even conduct simulated attacks or provocative movements around important chokepoints in the Strait of Hormuz or Bab el-Mandeb Strait. These trends suggest an emerging pattern of drone-enabled maritime attacks: using drones as a force multiplier (Chatham House, 2022).

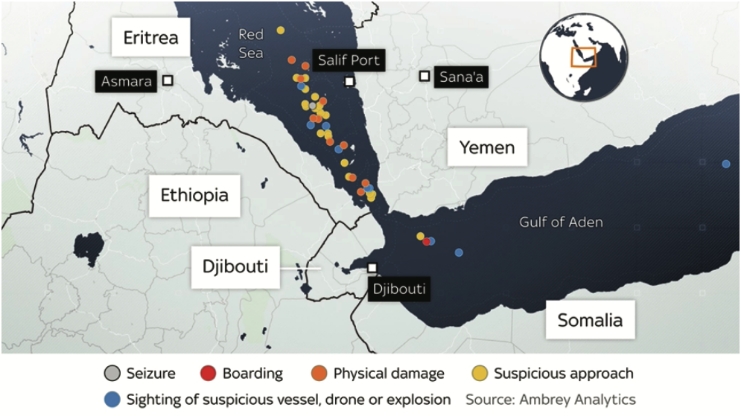

The question is no longer if drones will be used in maritime hybrid warfare. Drones are already there, taking advantage of the gaps between civil–military, inter-governmental, and corporate countermeasures. As shown in Figure 1, recent Houthi drone attacks have targeted chokepoints in the Red Sea, depicting 18 incidents, including drone, USV, and missile launch attempts intercepted in the southern Red Sea watershed. The vulnerabilities in existing countermeasures are that many of the maritime platforms that drones use as targets, such as ports and offshore energy infrastructure, are more exposed to the threat of drone-enabled soft power, have limited capacity for detection and protection against these attacks, and are digitally exposed to cyber-physical threats.

Figure 1: Reported Houthi drone and missile strikes across the Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb corridor (Nov 2023–Jan 2024). Source: Sky News, 2024.

II. Infrastructure Vulnerabilities: Soft Targets in Hard Waters

The Gulf’s maritime infrastructure, though sprawling, complex, and, more recently, increasingly digitized and networked, underpins national resilience in the Gulf littoral states and the global energy sector in general. The concentration of maritime infrastructure, the geography of infrastructure deployment, the increasing digital networked vulnerabilities that underpin critical maritime infrastructure operation, and the significant soft power effects of infrastructure strikes suggest vulnerabilities in the critical maritime infrastructure of Gulf states to drone-enabled attacks at sea. The four most notable points of vulnerabilities in Gulf maritime infrastructure are desalination plants, offshore energy platforms, commercial ports and logistic hubs, and submarine cables and underwater pipelines.

All four points are critical, civilian maritime infrastructures that are not hardened military installations or prepared for drone-enabled attacks. All four points of critical maritime infrastructure are also soft targets in that they are vulnerable to drone-enabled attacks at sea, are a major part of national resilience and economic and social lifelines for Gulf states, and their strikes have strategic outsize effects.

1. Desalination Plants

Desalination is key to water security in the Gulf; for example, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar source up to 90% of their freshwater consumption needs from desalination plants. These plants are located in or near coastal areas, are typically highly centralized, and lack hardened defenses. Because their SCADA systems for supervisory control and data acquisition are networked and centralized, they are soft targets for cyber-physical attacks such as malware,GPS spoofing, and precision kinetic strikes from drones (Chatham House, 2022).

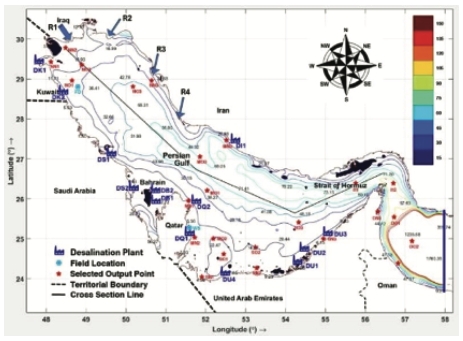

In a simulation conducted in April 2022 by the UAE, a mock drone swarm attack on one of the emirate’s major desalination plants was conducted. The outcomes of the simulation revealed that disabling two electrical substations could result in a water disruption to 1.2 million Emiratis and take over 6 hours to fix. This was a simulation, but the Emirati desalination plant’s infrastructure layout and operational timeline are likely a proxy for other plants in the Gulf as well (UAE Ministry of Defense, 2022). Figure 2 below shows how coastal plants, often located in shallow waters, present clustered targets that could be exploited by maritime drones (Lee & Kaihatu, 2018).

Figure 2: Locations of desalination plants in the Arabian Gulf over bathymetric contours (Lee & Kaihatu, 2018). Source: ResearchGate

2. Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms

Offshore oil and gas production infrastructure in the Gulf is attractive to asymmetric drone use because of their isolation, their flammable commodities, and their high market price per barrel. Iran and its proxies have demonstrated interest and ability in using drones near offshore energy platforms for coercion and political signaling.

Saudi Aramco reported in June 2021 that there were suspicious UAV flights approximately offshore energy platforms in the Safaniya oil field. The drones did not affect any infrastructure, but the threat was sufficient to stop operations and reroute helicopter logistics to the oil field. According to a CSIS report on offshore energy platforms, a single USV attack using shaped charges on key infrastructure components of an offshore oil production platform such as the Safaniya oil field could “disable a riser” or “ignite a platform fire, causing billions of dollars in damage in a matter of hours.”

3. Commercial Ports and Logistics Hubs

Ports such as the Jebel Ali port in the UAE, Hamad Port in Qatar, and King Abdul-Aziz Port in Saudi Arabia, are commercial ports, but in addition, these ports are also military logistics hubs for the GCC and serve to project regional power. They also have a heavy operational dependency on GPS, their digital networked dependencies for internal operations are high, and this, in combination with automated cargo handling and digitized SCADA networks, make them susceptible to hybrid drone threats.

In January 2023, the Jeddah Islamic Port in Saudi Arabia was forced to shut down temporarily after drones were sighted near critical port infrastructure. Although the drones did not attack the port, port officials evacuated the area, and as a result, port crane operations were suspended for a full 24 hours. Cargo was delayed, and some insurance and financial claims emerged. In this case, the drones had not achieved a kinetic strike, but their presence alone had significant financial and economic impacts.

4. Submarine Cables and Underwater Pipelines

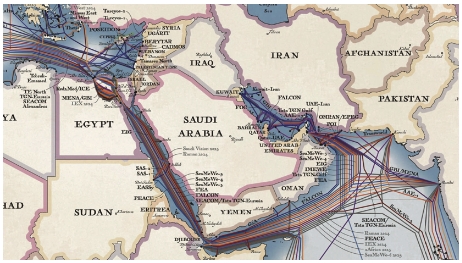

Submarine cables and underwater pipelines that crisscross the Gulf seabed support not only international financial and data-transit lines and business operations but also regional critical national security cables and pipelines. According to a 2021 NATO report, there has been an Iranian-flagged ship that repeatedly used a small UUV to approach undersea cables in the Gulf near Bushehr. At the time, there was no confirmation of sabotage, but being undetected to the proximity of undersea cable crossings was a capability in and of itself that presented a strategic message: A single strand of data cable out of hundreds of miles could, if cut, disconnect financial services, inter-GCC commerce, and delay military operations.

Figure 3: Strategic submarine cables and pipeline routes in the Arabian Gulf. Source: Middle East Eye (2023).

The vulnerabilities outlined above are not merely hypothetical. Regional proxy actors using increasingly precise and asymmetric drone tactics actively exploit them. This shift marks a new phase of maritime threat escalation.

III. Proxy Escalation and Drone Tactics

The proliferation of drone-enabled maritime attacks in the Gulf is not an accidental or arbitrary trend. It is a reflection of a larger proxy-militarization trend in which regional powers, notably Iran, are increasingly weaponing regional proxy forces to achieve security and foreign policy objectives without direct engagement or action. The instruments that these powers and regional proxies are leaning into are asymmetric in nature and use coercion, sabotage, and signaling to apply political and economic pressure to adversaries. The maritime space is highly attractive to proxy action because it offers an open environment, is hard to police in real-time because of the traffic density, and has a high level of under-protected civilian maritime infrastructure.

Iran’s Drone Doctrine and Naval Proxies

Iran has been highly invested in establishing a domestic drone ecosystem. According to the 2023 SIPRI report, Iran is capable of domestic production of loitering munitions drones, swarm-capable drones, and low-profile USVs and exports some of that capacity to its affiliated regional proxies, including the Houthis, Hezbollah, and Hashd al-Shaabi. These proxies act as strategic extensions of Iran to project power regionally and are used as instruments of indirect coercion and force multiplication. These proxies are given tools that are politically deniable but that can deliver a meaningful, asymmetric win at a low operational cost.The IRGC’s Naval Force, IRGC-N, has since 2019 also used drones in the Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman to shadow U.S. and GCC naval forces with reconnaissance UAVs and have installed drone launch pads on some of the man-made islands near Qeshm, a small island within range of UAE and Saudi energy and logistics platforms on the Strait of Hormuz, Abu Musa Island, and Hormuz Island (Chatham House, 2022).

Case Study: Houthis in the Red Sea

The Houthis have been using a significant number of drones in maritime operations. Houthis have launched more than 35 drone incidents at sea attributed to them, most of which target Saudi tankers or ports along the Red Sea between 2018 and 2024. In March 2022, a drone boat launched with explosives to use for a suicide attack against Ras Tanura was intercepted and disabled after having traveled 140 nautical miles using GPS guidance (Jane's Defence Weekly, 2024).

In January 2024, the Houthi strike against the MV Genco Picardy, a Greek-owned cargo ship in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, was a major escalation. A Houthi aerial drone attacked the ship’s bridge, injured two crewmembers, and were sufficient to cause a temporary rerouting of commercial vessels by several global shipping firms. This was a classic example of low-resource attrition conflict but with the strategic effects that can cause a force multiplier.

Hybrid Tactics: Surveillance, Disruption, and Denial

Proxy drone operations follow a hybrid operational model of probing defense and response, cyber intelligence and reconnaissance (ELINT), and kinetic attacks.

Drones are used to gather reconnaissance, run surveillance, harass, and ultimately cause persistent uncertainty. In addition to these functions, proxies have also used drones to force preemptive defensive measures, such as defensive deployments of naval forces in nearby areas.

Iranian proxies have since 2019 been using drones to surveil U.S. Navy ships or commercial tankers using reconnaissance drones, and U.S. officials have also confirmed instances of reconnaissance drones using loitering to scan offshore oil loading stations in Kuwait and the UAE to study blind spots and response time (Al-Monitor, 2022). The strategic pattern in most of these proxy incidents is not necessarily kinetic destruction but rather disruption. Forcing Gulf states to take defensive deployments, slowing operations, and shutting down ports result in asymmetric victories without the associated costs of war.

The vulnerabilities described above are not theoretical. In recent years, these critical systems have increasingly been targeted by proxy actors using unmanned drones in complex, asymmetric operations. These tactics often aim to cause disruption, impose political pressure, or test the response capabilities of Gulf states, all while maintaining plausible deniability. The emerging trend suggests that the line between conventional and hybrid maritime conflict is rapidly eroding. As these tactics evolve and proliferate, they necessitate structured policy responses that go beyond deterrence, aiming instead at pre-emption, resilience, and collective maritime governance.

IV. Policy Recommendations

The strategic and operational challenges that maritime drones present to Gulf states can be mitigated and neutralized to a significant extent. With the right mitigation steps, early warning, strategic alert, and countermeasures, the asymmetry in maritime drone usage that proxies and Gulf adversaries are enjoying can be reversed. This policy brief has made three recommendations for Gulf states to protect themselves and respond better against drone incursions. The three recommendations are the establishment of a GCC maritime drone intelligence and early warning network, the deployment of layered maritime drone defenses around critical infrastructures such as desalination plants and offshore energy platforms, and, lastly, institutionalizing joint civil–military simulation drills for maritime drone scenarios.

1. Create a GCC Maritime Drone Intelligence and Early Warning Network

GCC states are, at this time, not yet equipped with real-time warning, intelligence collection, and coordination systems on drone incursions in the maritime environment. This leads to long and slow responses, delays in attribution, and eventually leaves critical maritime infrastructure exposed to incursion and attack. This policy brief recommends establishing a GCC maritime drone intelligence and early warning network that shares real-time information, coordination, and collection on drones through a secure digital platform shared between GCC naval forces, coast guards, ports authorities, and energy companies. This network would integrate all currently operating radars, satellite data, AIS tracking, and other forms of passive drone monitoring for drones with more drone-focused RF and acoustic detection systems. It would also use open-source and forensic information to help attribute drone incursions to state and non-state actors and facilitate real-time information alerts to both government and private sector operators in cases of incursion.

Early warning is the first line of defense, and by making interconnectivity, information exchange, and secure real-time early warning alert more efficient, it would increase speed of response, reduce paralysis of operations at ports and platforms, and help with coordinated messaging in the event of an incident. All of the above contribute to deterrence, crisis management, and reputational defense.

2. Deploy Layered Drone Defenses at Desalina- tion Plants and Offshore Energy Infrastructure

Gulf states’ desalination plants and offshore energy infrastructure, most of which are in the Persian Gulf, are national security and economic lifelines. They are not military targets, but a successful drone attack on a single plant, which is entirely plausible, could have wide-ranging consequences on a massive number of people, cause panic, and serve as political advantage and blackmail. Gulf states’ desalination plants, offshore oilrigs, ports, and LNG terminals and liquefaction platforms are also in many instances not yet hardened against drone strikes, and in many instances, still rely on outdated and insufficient perimeter surveillance alone. Gulf states should rapidly establish layered defense systems around critical infrastructure such as desalination plants and offshore energy infrastructure.

The critical components of the layered drone defense system should include perimeter defenses against drones or USVs.

Perimeter defenses should be sensor-heavy and in addition to acoustic or RF-based systems for sensing approaching drones should include some short-range drone interception system such as net guns, microwave blaster weapons, or some directed energy weapons. In addition, GPS spoofing and jamming should be used to prevent physical cyberattacks by drones on SCADA systems and some form of cybersecurity integration to prevent digital incursions in case of a physical intrusion by a drone.

The unit cost for installing very basic counter-drone systems and infrastructure hardening measures pales in comparison to the potentially material economic and strategic damage of a successful attack. By taking these steps now, Gulf states could increase the cost of aggression on Iran and its proxies and enhance deterrence.

3. Institutionalize Joint Civil–Military Simulation Drills for Maritime Drone Scenarios

Response times and interagency and civil–military coordination are crucial when dealing with actual drone attacks, but because these systems have not been a large part of commercial port operators, energy contractors, and local emergency response units in the Gulf, they have not had the experience of dealing with drone incursions at sea in the Gulf. As this type of attack is now a part of the new normal, preparation for this type of incursion needs to become more serious, timely, and happen on a regular basis. This policy brief recommends institutionalizing joint civil–military simulation and annual joint maritime drone scenario simulation drills to be conducted in each of the Gulf states on a rotational basis. These should be: Conducted annually and on a rotational basis among GCC states with a particular focus on maritime drone scenarios: including UAV swarms over critical port infrastructure, USVs moving to attack LNG terminals, and GPS jamming at strategic points of shipping lanes Designed to include, in addition to capabilities for interception, also testing of evacuation procedures, cyber fallback protocols, and communication coordination for public messaging

Drills are a means of improving reaction times, providing hands-on training for all critical responders, identifying and closing critical gaps in command-and-control systems, and ultimately also sends a very visible signal to adversaries, a signal of strength, of resilience, and one that allows civilian responders to train for a conflict where they will be on the front lines.

V. Strategic Barriers to Implementation

While the proposed recommendations are necessary and urgent, several strategic and operational obstacles may hinder their implementation. Political fragmentation across the Gulf Cooperation Council remains a key challenge. Differences in threat perception, resource allocation, and national priorities have historically limited deep intelligence-sharing or integrated maritime defense planning.

A joint alert network, for example, would require not only shared infrastructure but also legal agreements governing real-time data exchange and situational awareness. Equally pressing are the financial and technological demands of building layered maritime drone defenses. Advanced radar systems, AI-based detection software, and coordinated air-sea drone interception technologies represent high-cost investments that may be unsustainable for smaller states without external support.

There is also a significant legal gap. International maritime law has not kept pace with the evolution of unmanned threats. Frameworks such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) offer only limited guidance on how states should classify and respond to drone activity in shared or contested waters. The principle of attribution, linking a drone to a responsible actor, is often unclear, especially in proxy scenarios. Without a shared legal understanding, pre-emptive or retaliatory actions against unmanned systems could provoke diplomatic fallout or undermine legitimacy.

VI. Conclusion

Ultimately, Gulf states stand at a crossroads. The same technologies that lower the threshold for maritime conflict can also serve as tools for coordination, deterrence, and regional resilience, if guided by a coherent, cooperative strategy. Drones at sea are no longer an emerging or speculative risk; they are a feature of the Gulf’s strategic environment. The Gulf region has seen all spectrums of drone use in maritime hybrid warfare: from reconnaissance drones, monitoring commercial ports to explosive-laden small USVs directed at offshore terminals. The key point about drones for all Gulf states is that they are more available and more affordable than they used to be, more scalable and deniable, and can cause outsize effects for states and non-state actors.

Gulf states have taken significant steps to harden their critical maritime infrastructure against drones and threats including maritime patrol aircraft, more drones, and increased aerial ISR coverage. However, their response and policy approaches to these threats are still in a fragmented and essentially reactive phase. The reason is that these attacks at sea and on critical maritime infrastructure present openings. They take advantage of operational gaps: operational gaps between civilian and military agencies, between energy and defense operators and critical national infrastructure, and between national maritime drone policies and a comprehensive regional approach.

The value of early detection and early warning in sharing real-time data on interdiction and response is far more valuable and crucial than ever, as these give governments and critical operators the best chance at preempting strategic surprises in a congested maritime zone. Defending Gulf energy and maritime infrastructure from drone incursions and attacks is no longer just a matter of technical readiness and preparedness; it is a matter of national sovereignty, credible deterrence, and regional reputation. Energy and security in the Gulf depend on how well this challenge is met in terms of speed, unity of approach, and determination.

References

- [1] Al-Monitor. (2022). Iran’s IRGC reportedly deploys drones to monitor Gulf shipping lanes. [online] Available at: https://www.al-monitor.com.

- [2] BBC News. (2021). Mercer Street: Deadly drone attack on tanker off Oman. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com.

- [3] Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2022). Iran’s Drone Proliferation Strategy in the Gulf. Washington, D.C.

- [4] Chatham House. (2022). Maritime Insecurity in the Gulf: Strategic Patterns and Emerging Technolo- gies. London.

- [5] Dryad Global (2023) UKMTO – Incident Warning, [online] Available at: https://channel16.dryadglob- al.com/ukmto-incident-warning [Accessed 2 Jul 2025].

- [6] International Maritime Organization (IMO). (2022). Cyber Risk Management and Autonomous Vessel Guidelines. London.

- [7] Jane’s Defence Weekly. (2024). Houthis Expand Maritime Drone Capabilities in Red Sea. IHS Markit.

- [8] Lee, W. & Kaihatu, J. M. (2018). Location map of desalination plants in the Gulf with the Gulf bathymetry.

- [9] NATO. (2023). Maritime Situational Awareness and Emerging Threats. Brussels.

- [10] SIPRI. (2023). Drones and Asymmetric Naval Warfare in the Middle East. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- [11] Sky News (2024) ‘Largest Houthi attack to date in Red Sea repelled by HMS Diamond’, [online] Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/largest-houthi-at- tack-to-date-in-red-sea-repelled-by-hms-diamond-grant-shapps-says-13045115 [Accessed 2 Jul 2025].

- [12] UAE Ministry of Defense. (2022). Joint Readiness Exercise: UAV Swarm Simulation at Energy Facili- ties. Abu Dhabi.

About the Author

Nasser Saif Al Kuwari is Research Fellow at the Center for International Policy Research (CIPR).

About Center for International Policy Research

Center for International Policy Research (CIPR) is a research center with focus on economic, politi- cal, energy and security issues in the GCC region. Based in Doha, CIPR specializes in political risk analysis, government and corporate advisory, conflict advisory, track II diplomacy, humanitari- an/development advisory, and event manage- ment in the GCC region and beyond.

The CIPR aims at becoming a primary research and debate platform in the region with relevant publications, events, projects and media produc- tions to nurture a comprehensive understanding of the intertwined affairs of this geography. With an inclusive, scholarly and innovative approach, the CIPR presents a platform where diverse voices from academia, business and policy world from both the region and the nation’s capital interact to produce distinct ideas and insights to the outstanding issues of the region.

Design and Layout: KARL

[email protected]